Introduction

I've been thinking about the internet a lot lately. Specifically, how it's evolved and how it might look in the future. I've also been re-reading the Tao Te Ching a good amount throughout the last year of quarantine so paradoxes have been driving a lot of my thoughts. I want to explain a paradigm that I've been using to think about the history and the future of the internet.

Dialectical monism is a school of thought that focuses on 2-part systems. It's commonly used to analyze history and other human-centered activity like debate around an idea. Dialectical monism describes situations where some action or idea comes about, called the thesis and then an oppositional idea arises in opposition to that thesis, called the antithesis. These anatagonizing views or events are then superceded by a synthesis. The synthesis represents a new worldview that exists and allows for both opposing ideas to coexist. It results directly from the antagonism between the thesis and antithesis. Some people represent this idea by saying that history is shaped like a spiral or helix, in that it tends to repeat, but never in the exact same way.

I really like this understanding of how paradigm shifts come about. It allows for a somewhat less structuralist and deterministic understanding of the future. I like to think of it as a predictive model that allows for some random variance in the output.

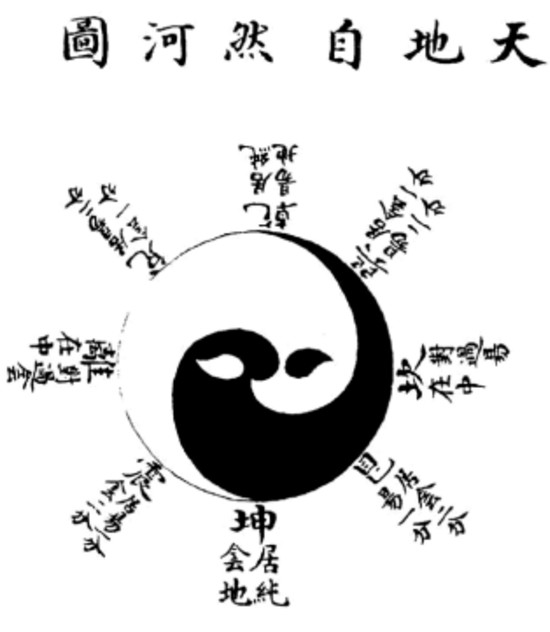

One great example of an implementation of this analysis system is the idea of Yin, Yang, and the Taijitu or, the combined whole created from Yin and Yang. Taoism acknowledges that, while forces can seem to be in opposition, they are both necessary to create the ultimate reality we observe as a result of that opposition. Allowing for a 2-part worldview is seen as necessary in order to create a more robust future.

I've been trying to view the internet through a similar lens lately. The design patterns that we've observed across the 2 phases of the internet, called Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, can appear to be in opposition. However, I think this opposition is only a driving agent. I think that we will settle into a more thoughtful and satisfying future on the web that represents a synthesis of what we've seen so far.

I don't think Web 3.0 will be a repeat of the Web 1.0, but I think the two may rhyme.

Table of Contents

Web 1.0: Yang

Yang is the active, the driver of change. It is rough around the edges and represents raw material that needs to be refined. I think the Yang lines up nicely with the early internet. I'll give some examples of live websites that I feel embody this nature. Some of these sites have been around since the early days of the internet, while others simply do a good job of conveying design principles of Web 1.0. I want to tease apart some of the ideas that have kept these sites around for so long or the content/design philosophies that cause them to remain rooted in the past.

Hacker News

The foremost example of a site that I think embodies Web 1.0 is Hacker News, YCombinator's news/forum site. YCombinator was founded in 2005 and Hacker News steadily increased in popularity since then. Today it is the foremost authority for community-driven tech industry. Users can share news articles and projects, ask questions to get community consensus, or discuss new developments and ideas in tech. Hacker News hasn't been around since the early days of the internet, but the principles of the site's design and content-management are great representations of the simplicity that drove the early web. It is a no-nonsense, minimal CSS, text-driven news site.

Oftentimes, simplicity breeds robustness. The minimalism of Hacker News' site design is quite brilliant in this way. It's a site created for nuanced discussions around the tech industry, often driven by employees of the largest tech companies. The user base is highly tuned to bad site design, so HN took the least controversial design approach.

The design for this site clearly presents a brand, organization philosophy, accessibility. I can access the site from my laptop, tablet, phone, or text-based terminal browser. And with each of those devices I will be greeted with pretty much the exact same experience.

The second you load up the site you can feel the values of the designers seeping through the screen. This also helps build an image of the audience for the site. People browsing the site likely favor calm technology that is built to last a long time and consistently serves its purpose. Something that can be odd about Hacker News for a first-time visitor in 2020 is the high density of information. Hacker News' homepage, on my 17 inch monitor, displays 25 article titles without a single thumbnail. That is almost unheard of on the modern web. The site does not coddle users or rely on visual stimulation to drive engagement. It exists to display news items and employs little frill when doing so. I don't mean to say that every site should have such minimal design, but it's notable the safety that design like this employs, while also making a site that's easy to maintain far into the future.

Compare Hacker News' homepage with Reddit's early UI. Here is an image of old.reddit.com, a mirror of reddit that shows the current site's posts with Reddit's original UI:

We'll come back to Reddit when we discuss Web 2.0, but I wanted to give an idea for how the early site used to look and point out that the original Reddit community was mostly made up of programmers or STEM students and now serves a much broader user base. People often lament the loss of the old UI because the barrier of entry created by the "bad" UI actually made for a sort of thoughtfulness filter. And I think that thoughtfulness was one of the original draws of the early internet. When you put an idea online it is very clear on sites like Hacker News, or early Reddit, that the thought must stand on its own two feet. Building communities around ideas is one of the most important features of being a person and browsing sites that shuffle around ideas thoughtfully create satisfying browsing experiences.

Also as a sidenote, the personal site of Paul Graham, the founder of YCombinator, is another great homage to the simplistic, easy-to-maintain design of the early web.

Textfiles

Another site that offers a look at some of the principles of the early web is textfiles.com. Jason Scott, a spokesman for the Internet Archive is the creator and maintainer of the site. This is another site that offers not only a giant cache of text-based content, but a clear window into the philosophy of its curator.

What can we learn about Scott's philosophy from this site? Well he certainly thinks that the internet was created to share information -- information created by other humans. The entire site is dedicated to sharing text-based files. These range from short stories to Ham Radio how-tos to hacking guides. The design follows accordingly and, again, shows a predilection towards robustness rather than decoration.

Another philosophical tenet made evident by this sites's layout is that the internet is meant for sharing any information. And since the internet is meant for sharing thoughts through files, of course there will be thoughts or documents being shared which are controversial. But beyond this, the site is simply an unopinionated cache of files that might be difficult to come across, presented with little design decadence.

In fact, lots of the allure of textfiles.com comes from its nostalgic black-and-green design (when viewed in a visual web browser). The site is meant to propel a user back to the bygone days of the internet captured by The Matrix and make a user feel like they are snooping around somewhere they shouldn't be. Reading the Anarchist Cookbook on the site feels super illicit (and I don't necessarily condone it!). This feeling is exacerbated by the aesthetic of the site and serves to draw a user in.

And again, like Hacker News, this site is extremely accessible. Here it is viewed from my terminal:

A large part of the importance of the internet comes from its ease of storage and indexing for information. Sites like textfiles facilitate the information retrieval process by curating information with little frill. Finding info on the site either by browsing or from a search engine is easy and fast.

Phrack

Phrack is an online magazine, or zine as they're sometimes called, first published in 1985. It famously platformed The Hacker's Manifesto in 1986 and still publishes issues today. The zine consists of staff- and community-written or contributed articles about web security and topics in web infrastructure.

The thing that's beautiful about Phrack is that it hasn't felt the need to update its design or its content-delivery methodology since its inception. Again, like Hacker News, the brand of the site lies in its almost luddite desire to work well rather than to be pretty. The site still serves the same purpose it always has and gets updated every time there's a new issue. It's built for the long haul.

As humans, we crave novelty from the internet or anywhere we get information. This experience of novelty within Phrack comes not from new visual stimuli for the site, but from the new ideas that are published in the zine. Sometimes persistence of ideas and sites can be hard on the web, but the minimalism in Phrack's design has allowed it to stay agile throughout all of the changes to the web since it was founded.

The Tildeverse

The tildeverse is a bit odd. It's not just one site, but a federated group of websites. Well actually it would be more accurate to call it a federated group of servers. Each tilde site is just a computer, just like each website runs on a computer hosted somewhere in the cloud. The difference between a tilde and a website, though, is that users of a tilde get to use the entire computer. Web apps today are typically run on a dedicated server. This means that the site is run on a computer and all of the software running on that computer serves the purpose of running the website. Sites within the tildeverse have homepages that can be viewed from a browser, but they also allow users (nearly) full access to the entire computer that runs the website.

This video explains things better than I can do here.

You can think of sites within the tildeverse like a storefront to a club. The public face of the organization is just one small piece of the actual enterprise, and real benefit comes from accessing member areas. The storefront is like the webpage and the member areas are other services and areas within the server running the website.

Tilde sites offer membership via login credentials to access the server that holds their website. Once logged in, the server has BBS boards, IRC chatrooms, individual user blogs, gopher pages and blogs, radio stations, and programs created by the users to run on the server. They're a great deal of fun and they're run by a bunch of really kind and smart people.

Let's take a look at a single tilde site, tilde.town.

As we saw from the other sites, this homepage is pretty off-putting. Maybe the most off-putting of the sites we've seen. But that's because this site isn't meant to just be viewed from the browser. If we have user access to the server (sign up here if you're interested!) we can access the full suit of the content being created by users on that server.

Here's my homepage when I use ssh to login to the server:

And here's the actual site homepage viewed from a terminal browser:

The main takeaway from the Tildeverse that I wanted to highlight is that it allows for centralization in a very different way than we usually see today. Centralization today takes the form of a couple of companies that own massive server infrastructure which power lots of apps across the internet. Tilde sites are centralized in that users have access to a variety of services all in one place.

Compare this to the modern web where a user from twitter interacting with someone on Facebook or Letterboxd would have to know the user's individual accounts on those sites to interact with them and make separate accounts for each site. Tildes allow the same users to interact across a myriad of services all contained in the same place. If you're interested in exploring these sites, check out the Tildeverse site or SDF for an alternative.

Paul Ford, the inventor of tilde.club has a great analogy in his blog post about starting the server that contrasts websites and server use today with the idea of tilde servers:

Fast forward 20 years: Your typical “cloud” Unix server, designed in the 1970s to be a very social place, is today a ghost town with one or two factories still clanking in the town square—factories that receive our email, or accept our Instagram photos and store them, and manage our data. But there’s no one walking around and chatting downtown. Thus when people talk about “cloud computing” they are talking about millions of tiny ghost towns. Ironic, because what do people build on these ghost towns but social networks.The Zen of Raw Text

So what kinds of patterns did we observe from these early web sites?

These sites are extremely robust. They've found a way to create long-lasting bastions of information by doing as little as possible in the way of design. This sort of philosophy can lead to a much longer persistence of ideas, which are ultimately the lifeblood of the internet.

These sites are extremely accessible. I can view them on any device and get pretty much the exact same experience. A screen-reader would have no trouble delivering all of the content on these sites. One can consume the ideas exactly the same as someone using a brand new Macbook and the latest version of Chrome.

These sites are based around text/information. When images are used on one of these sites, they are the main main content on a page. Blog posts on these sites are a bit longer because text-based ideas are first-class citizens. This abundance of text-based ideas leads to more thoughtfulness in posts or otherwise a more stream-of-consciousness writing style. At a minimum it leads to a very narrative-driven browsing experience that feels satisfying in the same vein as reading a long-form article on the modern web. This sheer amount of raw content generation drove the internet to become the honed-down machine that we know today. These sites offer a lot of raw material being thrown at the canvas of creativity.

Now I won't claim that longer = better 100% of the time when considering a blog post or article on the web. But both consuming and generating a longer piece of media tends to be a bit more of a mindful and meditative process. Blogging in this manner and publishing content resembles the journaling process a bit more closely than the content creation process that we see today.

Web 2.0: Yin

Yin is the passive, the receiver. Here I'll talk about how I think this parallels the modern web.

Social Media

Social media was able to take one of the hardest-to-define principles of the early web and expand on it. That principle is the ease of content generation and the creation of a network with which to share that content.

Anyone can easily sign up on Twitter today and immediately publish a thought that is available within their network and the entire internet. However, the main sources of links to each tweet are other tweets. Facebook is an even more pure example of this encapsulation, since posts are not typically available from a browser or linkable except from within Facebook. Social media sites have become a bit of a wrapper around web content -- sort of a mini self-contained internet. In addition to this platform-specific idea encapsulation, the style of content is much different on the modern web. Content is much more visually-based and posts are typically shorter than average user posts from Web 1.0 sites.

The purpose of this shift in content style is two-fold: to allow a vaster portion of the public to share ideas by decreasing storage size, and to improve the user experience of the person consuming the content.

It's far easier both to create a 280-character tweet and to read it than it is to read a long blog post article. Content has a much more stream-based structure and is meant to be easily digestible.

For an example of this multimedia-centric, stream-of-content approach, let's take a look at Reddit's current UI:

Contrast that with the original UI shown earlier and we start to see what values have been selected for in the modern web and how users tend to consume content.

A really interesting contrast that shows what trends have been observed in people browsing the internet and how to target for a larger portion of the web as an audience.

Now I don't mean to imply that this sort of UI and content presentation is a bad thing. It inspires lateral thinking in content generation and makes for tremendous new additions to art and humor. And there are ways to get around the limits of this stream-of-content model if people really want to. Twitter threads are common, Instagram allows stories and multiple images to be displayed in albums. But it is notable that the concept of online interaction between people was pulled out of the old web and turned into a celebrity on the modern web. Where before we saw awkward BBS forums and IRC chatrooms, we now see sprawling, polymorphic content jungles tailored to individual users.

Centralized Hosting (Hardware as a service)

The other pattern that demonstrates the state of the modern web, in my opinion, is the current state of web hosting.

It's an industry that was, quite literally, created as a budded lifeform off of some of the first internet companies. It's no surprise that Amazon, Google, and Microsoft offer the largest cloud hosting infrastructure on the planet -- they were some of the most successful early adopters of the online business model.

Smaller users and content creators have benefited from this centralized hosting as well. I'm running this site with GatsbyJS on AWS Amplify, because that is the easiest way that I've found to deploy a site to the web. We're extremely lucky to have access to these hosting services and they make not only content publishing easier, but the entire process of creating platforms for online thought sharing.

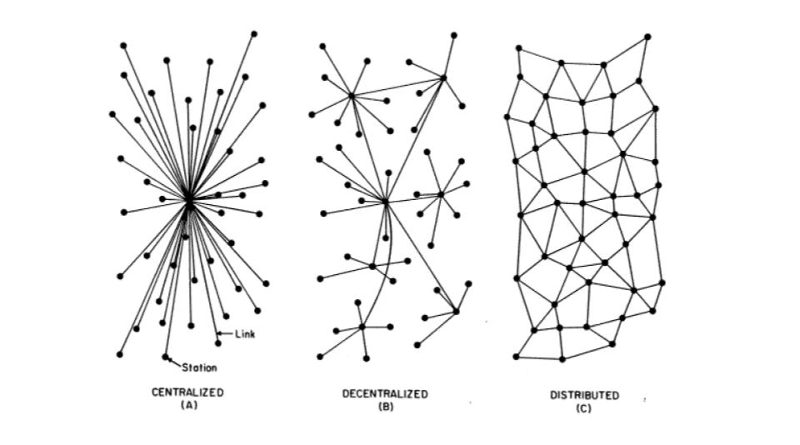

Sites are much more scalable now because of services offered as abstractions through things like AWS that allow resources to grow with userbases. So if we think about the web as a network we can consider that the modern web has several infrastructure nodes that make up the lionshare of the volume of sites. This centralization has made things a lot easier for the day-to-day user of the web and creator on the internet. However it comes with the tradeoffs that centralization always have. Publishing ideas is very easy today, but publishing is a bit more limited either by a site or within the resources offered by a hosting service.

Additionally, there are risks, when a large amount of traffic in a network is routed through a small number of nodes, but I won't talk too much about that today. Instead I'll talk about the design paradigms that have been selected for in the modern web.

New Definition of Minimalist Design

The sites we saw in the Web 1.0 section were certainly designed in a minimal way. But that was a minimalism of the design process. Now we see sites that are extremely thoughtfully designed to appear visually minimalist.

What I consider to be the modern web is the set of sites that have allowed user experience and design to become a first-class citizen. This has been accomplished over the years through an evolution of the web that has come to understand how the human brain interacts with websites. Sites are designed now to accommodate the user experience in a way that accomplishes a goal for the owner of the site while also maximizing satisfaction for the user.

A perfect example of this minimalist design approach is Google. Google is an interesting example too, because it began its tenure as a site on the early web that was truly a minimal design for robustness' sake. The Google homepage is essentially a single search bar at its core. But it is also a canvas. There have been thousands of Google doodles over the years that have all fit around the functionally unchanged Google searchbar. The modern web is characterized by this minimalism of design that allows for visual creativity.

JavaScript

One curious feature of the "minimalization" of the modern web is that, through the pursuit of a perfectly minimal user experience, some of the semantics of the internet have been fudged a bit in order to focus on this minimal design.

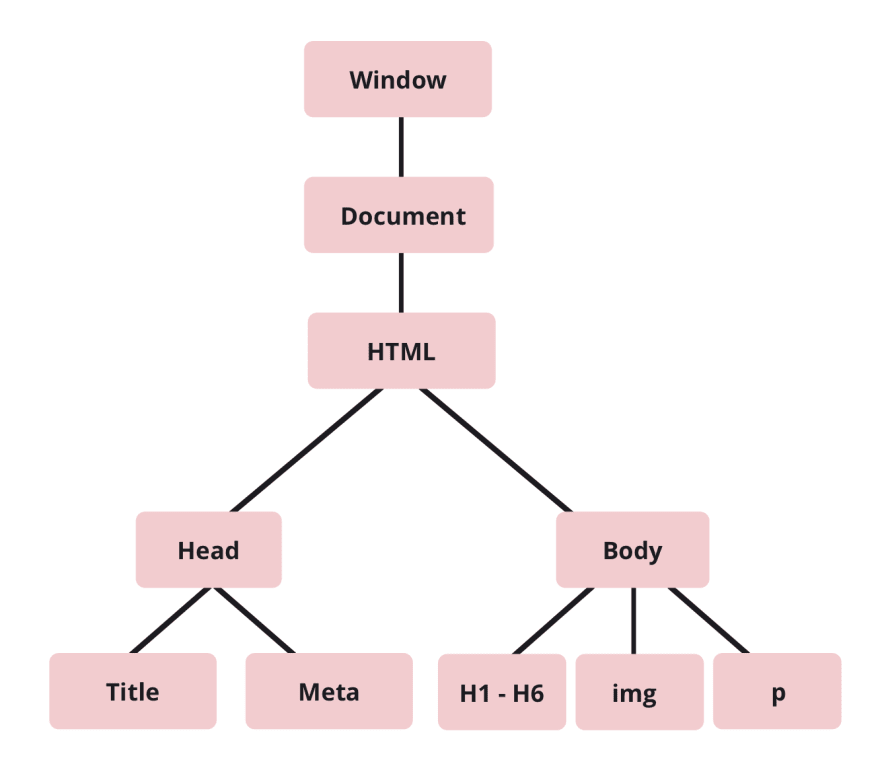

JavaScript was created in 1995 but exploded throughout the early aughts when developers began to understand how useful it was in making the web responsive. Webpages became far more dynamic and allowed not only improved design within the canvas of a webpage, but for that design to be responsive. The DOM became a data structure that developers could manipulate as they pleased and create a truly dynamic experience for a given webpage.

The Rise of the <div>

How is JavaScript able to manipulate the web so effectively? Well one pattern that has emerged is the heavy reliance on the <div> tag in web development. JS is extremely effective at moving around and editing any type of DOM node; <p>s, <ol>s, <article>s, etc. But the advantage of sticking items into <div> tags is that they become a much more ambiguous functional units for a given webpage. A <div> represents "whatever I want to put here", rather than a semantic tag that explains what an element is. This is, at least partially, a response to the changing definitions of the web and the different styles of information that is now displayed on webpages. As such, most of the web you see today is build with <div>s. They're kind of like the lego blocks of the internet.

Similarlly, here is the homepage of the New York Times viewed from a terminal browser:

We see a well laid-out site from the visual browser, but viewing on a less visually-based browser creates some serious headache.

This design pattern isn't necessarily a bad thing on its face either. Heck, most of the design I do on the web prominently features <div>s. This shift from semantic tags to relying on <div>s came about, in large part because HTML tags were created edit text-forward sites like we saw in the last section. Hyper-TEXT Markup Language. But the internet today revolves around so much more than just text. Take this site, for example. There isn't an HTML tag that defines <particle-background>, so I (read: the maintainer of this libary) had to get creative with <div>s.

The Zen of Good design

Because of this increased demand for a visually pleasant user experience, design systems have been created and employed by corporations that have helped design the modern web. The web looks a lot better today because the psychology of the user experience has been brought to the web.

Businesses did not have much interest in having a presence on the early web, but now the opportunity to increase capital via the web has been made abundantly clear. This means, of course, that more of the internet is now devoted to advertising and controlling a user experience in a way that results in sales conversions. But it also means that everyman developers like myself have access to the same tools that corporations use to build the largest retail sites and markets in the world.

Yes, corporations moving online meant that some space had to be carved out in the internet zeitgeist for these corporations to continue to sell ads and products. But at the same time corporations couldn't help but have the open-source pioneering spirit of the internet rub off on them in the process of moving their focuses online. React is a web-design framework that I love and use everyday. It also happens to have been built and maintained by Facebook, one of the largest companies in the world. This doesn't mean that it doesn't have an incredible user community built around keeping it up-to-date. It just means that it has people with some financial incentive to deliver better products to the open web.

Web 3.0: Taijitu

Why Thoughtfulness Is Important on the Web

I believe that the content generation process and the content consumption processes are both most satisfying when they are thoughtfully done. This isn't something that is completely missing from Web 2.0. You can still read longform articles and user blogposts. But these longer, more thoughtful content pieces tend to be produced by groups coming from different mediums and as such tend to include paywalls. Otherwise they are centralized platforms that incentive user-engagement and lead to a polluted content space filled with infighting centered around beginner tutorials.

And our biology tends to drive us towards less thoughtful media for content generation and consumption. It's easier both cognitively and technologically for a user to read 5,000 words a day on Twitter, than it is for them to read the same amount spread out over a few blog posts or articles, but it feels like less immediate work. Longer form media requires a bit more thoughtfulness and discipline to achieve the full consumption. This means that we tend to consume ideas much more like a stream than like a narrative.

Single disparate thoughts create a bit of an unfulfilled feeling when browsing them for a long time, but they're easy to consume and the lack of division between thoughts means this can be done for long periods of time without realizing that much time is passing. In my experiences though, people tend to find more satisfaction from consuming a larger volume of ideas within a specific piece of media (like this blogpost hopefully). Larger ideas create an experience of following a narrative and reach a more satisfying conclusion. They also allow for more nuanced opinions to be shared than a short blurb that condenses the same idea.

We're at an odd juncture for neuroscience on the web because we've made it incredible easy to consume a vast amount of information, but without the satisfaction that usually comes from doing so (such as reading a book or watching a movie). The human mind has been allowed to experience extremely thoughtfully designed visual narratives as we navigate sites on the modern web, but in the future I think this visual narrative can be combined with thoughtful narrative of text as well in a way that allows content to be satisfying over longer stretches of consumption. In a sense I hope to see a Web 3.0 that combines the most Zen principles of Web 1.0 and 2.0.

Let's talk about two tenets that may or may not come to embody Web 3.0 and how those technologies can best harness what we've learned about the experience of browsing the web.

The Semantic Web

Sometimes the desire to create a visually pleasant web experience can burrow our design into traps. It's easy to design a site that is beautiful and responsive. But the second another device is used or the screen size changes, we see behavior we didn't account for. Screen-reader users on the modern web are met with an almost incomprehensible slog of anonymous <div> tags that don't seem to represent any coherent path through the page.

Design systems can be extremely useful for mitigating this, and indeed I think the reliance on these systems will continue to grow as the web expands to encompass responsive design principles for free, but we need to see an increased effort to make design accessible and semantic. The semantic web is the way forward.

This is especially important if we consider the right to scrape. It's easier now than ever before for information to be scraped from the web for an infinitude of purposes. And this is despite the difficulty of parsing the web semantically. I think in the future we should strive to create a web that makes sense to machines as well as people. With Web 2.0 we made an internet that is extremely easy to use for humans, but I think as time goes on and more people use other sites' APIs and data as tools to build new programs and tools of their own, we need to see a shift towards creating sites that can algorithmically be parsed. This lends to the idea of accessibility as well. If a site can be easily parsed to scrape data, then it can be easily parsed to read contents to a disabled user.

I know I mostly touched the semantics of HTML page layout and not the full protocol definition of the Semantic Web. It's a super interesting topic that I may write more about in the future, but for now you can read more about it here.

Decentralization & The Distributed Web

The final technology that I think will carve out the future of the internet is the decentralization or distribution of the web.

The decentralized web resembles Machine Learning to me more than any other principle. Research in machine learning has been going on since the dawn of computers. But the term has only become a vernacular word in the past 5 years or so. This is due to software and hardware advances that have made training deep neural networks much more feasible. This decreased computational burden has allowed machine learning to become a commonplace member of commercial web applications.

And just like machine learning, decentralized computing and distributed filesystems have been around for quite a while. They just haven't seen commercial integration yet. Probably the largest usecase for decentralized storage and computation is that of Peer-to-Peer networking, used in torrent hosting and sharing.

Now we see distributed filesystems and platforms taking their first fledgeling steps outside of that usecase in the form of sites/projects like Interplanetary File System, Mastodon, and the Solid Project. These platforms are mostly considered to be fun hacked together toys, used by a small contingent of few tech-savvy hobbyists. That should sound extremely reminiscient of the internet and computers in general. Both were seen, before commercial adoption, as fancy novelties for novelty's sake with little real-world application.

Just as machine learning went from an academic study to a practical tool in the form of community dev libraries like PyTorch, Tensorflow/Keras, and fast.ai, I think decentralized/distributed infrastructure will become a platform that allows easy content generation and consumption once once the right abstraction comes along.

Lots of infrastructure pushes for this have already begun. Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the world-wide web has invested a significant amount of time and capital into creating Inrupt, a start-up built around the decentralized platform Solid, which is a decentralized platform built at MIT. In addition, the Interplanetary File System project has been gaining momentum in the past few years by researchers who have realized that datasets orders of magnitude larger than previously possible have become available when hosted in a distributed fashion. I think somewhere in the primordial soup of these blossomming decentralized platforms lies the future of the internet as we know it.

Some Final Design Principles

So are we doomed to face the exact same cycle of pure text-based content followed by an eventual corporate stimulus of design for the decentralized web? I don't think so.

We've learned a ton about creating forums for ideas on the web that can be transferred to the decentralized web. But my hope is that we move towards this new incarnation of the internet with the human experience in mind and not just the experience of a user being guided to a sale. The decentralized web brings an incredible opportunity to improve upon the internet as we know it today and reclaim some sovereinty over the content that we consume and generate. I believe that the decentralization of the web will rekindle some of the curiosity that pushed us onto the web at its inception. And I think when we make it there, we will be able to create a more satisfying experience everyone using the web.

At the end of the day, the internet is a network, and that network is a reflection of us. So as time goes on the internet will evolve to better reflect the information that it houses and that information is us. I'm excited to see what we look like next.

All the best, Mickey

P.S. As a disclaimer for this post, I want to make it clear that I do not practice every single thing that I've preached in this post. I am working on improving the accessibility of my site for text-based users and I use a hosting service with a static site generator to alleviate much of the work for myself. In the future I will be looking into things like Bearblog for creating a text-friendly alternate to my personal site, but for the time being I'm just a frontend developer who is trying to share some things I've noticed.